A spinal cord injury (SCI) is a life-changing injury that often changes the way you interact with the world. In general, life expectancy following and SCI has improved significantly in the past century, however, the years lived with additional disability are apparent[i]. How you mobilize is the most easily identifiable change. Less apparent changes like your social status or the role you play in your family can be just as metamorphic.

Keeping on top of our health as we age can be difficult. Remaining physically healthy and mobile as the normal aging process takes effect on our bones, joints and muscles requires vigilance. Otherwise, daily tasks that we may have taken for granted in our younger years, like bathing, or walking up and down stairs, can become challenging or even impossible.

A spinal cord injury accentuates the barriers associated with aging and create greater challenges for an already overwhelming process. In this blog, we look at the five changes a person with SCI undergoes as they age, and key strategies to support healthy aging for a person living with SCI.

Table of Contents

- Long-term effects of chronic spinal cord injury

- Secondary health conditions of the original injury

- Other conditions unrelated to the actual SCI

- Degenerative changes

- Environmental factors

- Three key strategies for supporting healthy aging with SCI

Five Changes a Person with SCI Undergoes as They Age[ii]:

1) Long -term Effects of Chronic Spinal Cord Injury (SCI)

After a spinal cord injury, a person’s mobility may change significantly. A wheelchair or gait aid can become the main means of navigating the community or home space. As a result, people with SCI are at a higher likelihood of developing repetitive strain disorders, overuse injuries. There could also be at a higher risk of falls.

Other possible long-term effects of SCI, as a person ages, is poor bone health in areas below the level of injury. Additionally, recurrent bladder infections may be associated with less compliant tissues and immune systems as we age. For instance, pressure ulcers can lend themselves to people with SCI far more than the general population due to increased immobility and increased shearing forces from boney prominences. That, paired with a less robust collagen/integumentary system will increase the likelihood of developing these issues later in life for a person with SCI.

These long-term effects of SCI listed above are just a handful of things to look out for associated that often worsen with an aging body with SCI. Neuropathic pain, cardiovascular health, and interactions between several systems across the aging timeline further complicate how a person with SCI ages in a healthy manner.

2) Secondary Health Conditions of the Original Injury

As a person with SCI ages, there are specific and progressive things that can occur that are directly related to the original injury to the spinal cord. For example, a syringomyelia occurs when a fluid filled sac develops around the injured spinal cord. This sac can build up in pressure and further cause more damage to the spinal cord, resulting in increased symptomology throughout the lifetime.

After SCI, some people may have instrumentation such as rods, pins, and different forms of medical hardware to keep the vertebrae and joints of the spine in a correct position. Over time, these pieces or hardware may need to be adjusted or revised, depending on how the body naturally ages.

3) Conditions Unrelated to the Actual SCI

Medical conditions associated with SCI have a large overlap with long-term effects of living with SCI. If the long-term effects of living with SCI reach a threshold of severity, a person with SCI may further develop other medical conditions.

For instance, increased body weight and decreased muscle mass is statistically associated with the SCI aging population. If severe enough, a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes may be established for the person and additional interventions and medical guidelines would need to be established.

In addition to this scenario, chronic heart conditions associated with less physical activity/ mobility can further push a person with SCI to be formally diagnosed with heart disease or hyperlipidemia.

Lastly, from a muscle and bone standpoint, limited exercise, weight bearing, and, calcium re-uptake may lead to a diagnosis of osteopenia/osteoporosis, in addition to sarcopenia. This means that bones may become less strong, and muscles have less strength, overall.

4) Degenerative Changes Associated and Accelerated with Aging

Degenerative changes associated with SCI relate to things like osteoarthritis and tendinopathies in specific areas of the body. Shoulders, elbows, wrists, and fingers often accelerate in degeneration due to additional use over the lifetime. These areas of the body are often accelerated in degeneration due to things like wheeling, transferring, and an increased dependence on the upper body for mobility or ambulation purposes.

5) Environmental Factors that Complicate Independence While Aging[iii]

It is clear that after an SCI, societal and family roles may change. In addition, cultural barriers can impact how well a person reintegrates into society as they age. As one ages with and SCI, there is a higher likelihood to become socially isolated if social supports are not established early, and often.

The impact of a SCI does not only affect the individual, but their family and community members around them. Negative societal stigmas may, unfortunately, encourage learned disability and learned dependence.

Key Strategies for Supporting Healthy Aging with SCI

With advances in medicine and rehabilitation, more and more people living with SCI are living longer.[iv] In order for healthy aging to take place, it’s important to understand the changes listed above, and follow some key strategies to help reduce the degree to which body systems lose their functionality with age.

1) Regular Check-Ins with Health Professionals

Following up with health professionals and attending appointments that maintain your neurological and physical health should be a priority. Similar to check-ins on medications or specialist appointments, some individuals may require reassessments to determine which pieces of equipment or medication are necessary for the progression of their SCI rehabilitation.

Missed appointments have deleterious effects on outcomes for rehabilitation but are also costly to the medical system. Studies have shown correlates to missed appointments, such as severity of injury, etiology of the SCI, and demographics[v]. Collaborating with health professionals to decrease these barriers to attending appointments should also be a priority.

Check-ins with physiatrists, neurologists, and therapists that have additional training and experience working with people living with SCI is important throughout the lifetime. For example, physiotherapists and occupational therapists who are trained in wheelchair modifications, home adaptive equipment (e.g., bathrooms and beds), and any additional exercise equipment will be able to guide any changes to these pieces of equipment throughout a lifetime.

What someone is able to do at early stages of injury may be different as they are in later ages of injury. A primary example would be an assistive device like a mechanical lift vs a transfer board. A transfer board would be an example of how a person with SCI transfers independently whereas a lift would indicate the need for more assistance.

You may also enjoy reading: Healthy Aging – A Holistic Approach to Aging Well

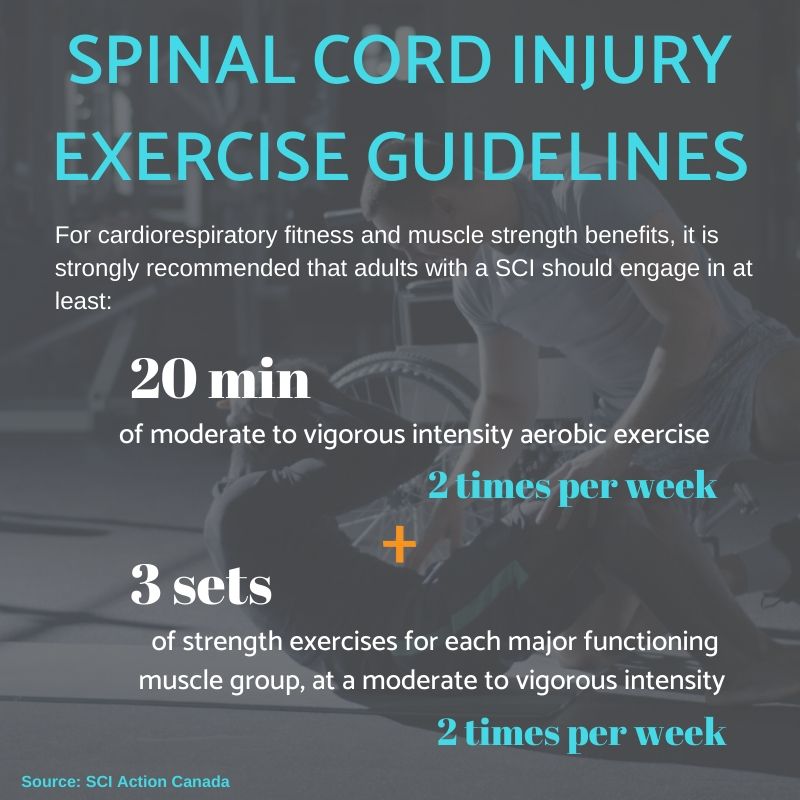

2) Meet the Physical Activity Guidelines for People Living with SCI

Improving cardiorespiratory, cardiovascular health, and musculoskeletal health can lower the likelihood of developing secondary complications associated with SCI across a lifetime. Integrating the physical activity guidelines for people living with SCI is a fundamental and first step to ensuring we are giving ourselves the best outcomes while aging with an SCI.

Physical activity guidelines are not just for adaptive sports or games—although highly encouraged! They can be things like gardening, daily chores, and even wheeling around the neighbourhood with family, friends or pets at an intensity that provides a physiological benefit. These guidelines are meant to guide all people living and aging with SCI, regardless of injury level.

3) Advocate for Better Access to Support and Services

Improving your independence is an important part of healthy aging. Too often, people with SCI struggle to find adequate support or access basic services that allow us to participate fully in the community.

At Propel Physiotherapy, we assist our clients in navigating physical or policy-based barriers to activities. Educating the general public and healthcare community on spinal cord injury and advocating for improving the lives of people living with SCI is part of our mission. We also encourage our clients to advocate for themselves. These strategies are in line with healthy aging for people living with SCI, and go beyond the injury itself.

Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation

According to the Rick Hansen Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) Registry 2019, there are over 86,000 Canadians living with spinal cord injury. Regaining and maintaining your quality of life after spinal cord injury involves many factors and a multi-pronged approach.

The physical rehabilitation of spinal cord injury requires both specialized training and equipment. At Propel Physiotherapy, we combine our knowledge and passion for working with people with spinal cord injury with cutting-edge treatments and technologies. This enables us to provide high-quality comprehensive care in both our clinics and out in community settings.

If you require additional information or have more question on how Propel Physiotherapy’s services can help, contact us for a complimentary consultation.

References

[i] McColl MA, Charlifue S, Glass C, Savic G, Meehan M. International differences in ageing and spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2002. 40:128-136.

[ii] ibid

[iii] Praxis Spinal Cord Institute. Rick Hansen Spinal Cord Injury Registry – A look at traumatic spinal cord injury in Canada in 2019. Vancouver, BC: Praxis; 2021.

[iv] Hammond et. al., Missed Therapy Time During Inpatient Rehabilitation for Spinal Cord Injury .Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2013. 94(4).S106-S114.

[v] ibid

Written by